Treaty Of Madrid (5 October 1750) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Madrid, also known as the Treaty of Aquisgran, was a

The heavy taxes imposed on all goods officially imported into Spanish America created a large and profitable

The heavy taxes imposed on all goods officially imported into Spanish America created a large and profitable

commercial treaty

A commercial treaty is a formal agreement between states for the purpose of establishing mutual rights and regulating conditions of trade. It is a bilateral act whereby definite arrangements are entered into by each contracting party towards the o ...

between Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, formally signed on 5 October 1750 in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

.

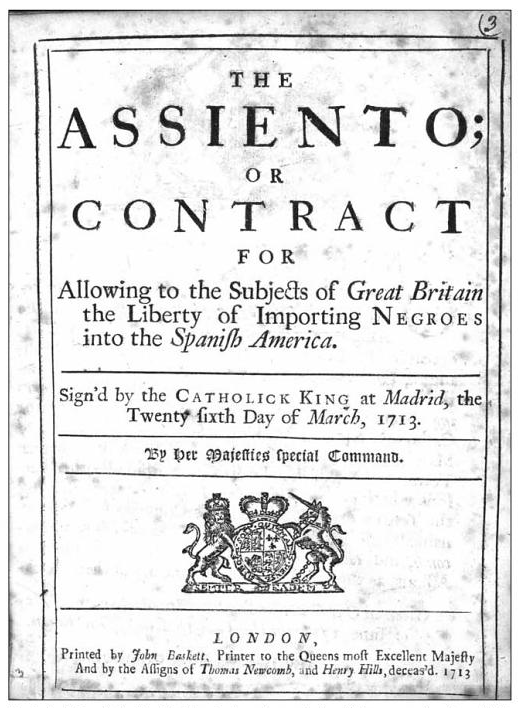

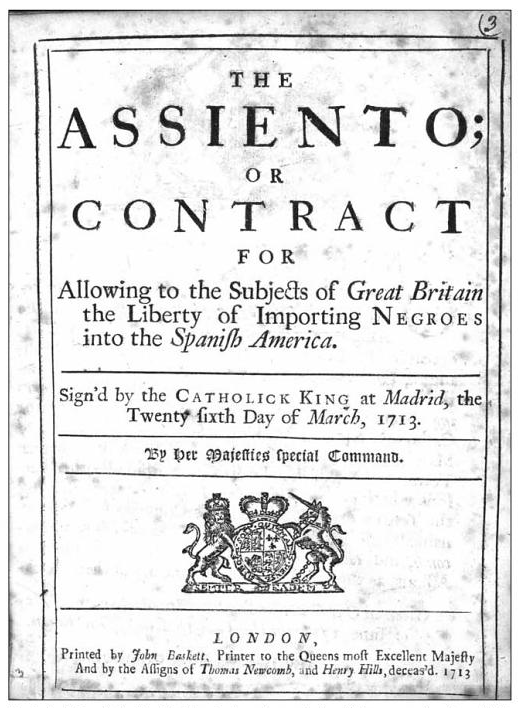

Commercial tensions over the ''Asiento

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide African slaves to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the trans-Atlantic slave trade directly from Afri ...

'', a monopoly contract allowing foreign merchants to supply slaves to Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' Spanish Empire, imperial era between 15th century, 15th ...

(which was granted by the Spanish Crown to Britain via the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

), and alleged smuggling of British goods into Spain's American colonies led to the War of Jenkins Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

in 1739. This was followed by the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's W ...

, ended by the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

In addition to the ''Asiento'', there was also a substantial import and export trade between Spain and Britain, carried out by British merchants based in Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

. Due to an error by negotiators at Aix-la-Chapelle, the treaty failed to renew their trading privileges, which were treated as cancelled by the Spanish. Both sides also claimed they were owed large sums of money in regards to the ''Asiento''.

However, the trade through Cadiz was equally important to Spain, while Ferdinand VI

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Savoy

, birth_date = 23 September 1713

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Villavici ...

, who succeeded as king in 1746, was more pro-British than his predecessor. This allowed the two sides to reach agreement on a new treaty, which restored trading privileges, while the ''Asiento'' was cancelled in return for a one time payment of ÂŁ100,000 to the British.

Background

The 1713Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

awarded Britain merchants limited access to the closed markets of Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' Spanish Empire, imperial era between 15th century, 15th ...

; these included the ''Asiento de Negros

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide African slaves to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the trans-Atlantic slave trade directly from Afri ...

'' to supply 5,000 slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

a year and a ''Navio de Permiso'', permitting limited direct sales in Porto Bello and Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

. The South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

established to hold these rights went bankrupt in the 1720 'South Sea Bubble', and became a state enterprise, owned by the British government.

The heavy taxes imposed on all goods officially imported into Spanish America created a large and profitable

The heavy taxes imposed on all goods officially imported into Spanish America created a large and profitable black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the se ...

for smugglers

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations.

There are various ...

, many of whom were British. The ''Asiento'' itself was marginally profitable and has been described as a 'commercial illusion'; between 1717 and 1733, only eight ships were sent from Britain to the Americas. The real benefit was that its ships were allowed to import goods customs-free.

However, the Spanish tended to arrest any vessels caught with illegal goods, regardless of whether they were technically chartered by the South Sea Company, while other traders smuggled slaves, undermining the monopoly granted by the ''Asiento''. The result was a series of claims and counter-claims; by 1748, the British argued they were owed nearly ÂŁ2 million by the Spanish Crown, which claimed equally large amounts the other way.

These commercial issues led to the outbreak of the War of Jenkins Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

in 1739, which became part of the wider War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's W ...

in 1740, and the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle largely failed to remedy them. Although the ''Asiento'' was renewed for four years, the South Sea Company had neither the desire or capacity to continue; of far greater importance was the import and export trade carried out by British merchants based in Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

. British goods were imported for re-sale locally or re-exported to the colonies, Spanish dye and wool going the other way; one City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

merchant called the trade 'the best flower in our garden.'

Lord Sandwich

Earl of Sandwich is a noble title in the Peerage of England, held since its creation by the House of Montagu. It is nominally associated with Sandwich, Kent. It was created in 1660 for the prominent naval commander Admiral Sir Edward Montagu ...

, lead British negotiator at Aix-la-Chapelle, failed to include the Utrecht terms in the list of Anglo-Spanish agreements renewed in the Preliminaries to the treaty. When he tried to amend the final version, the Spanish refused to approve it, threatening the lucrative import and export trade between the two countries. However, both sides wanted to resolve the problem, since the trade was equally valuable to Spain, while Ferdinand VI

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Savoy

, birth_date = 23 September 1713

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Villavici ...

was more pro-British than his French-born predecessor Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain, also Philip V, Duke of Burgundy (1526–1598)

* Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was ...

.

José de Carvajal y Lancáster

José de Carvajal y Lancáster (1698–1754) was a Spanish statesman.

Biography

He was son of the Duke of Liñares and his mother was descendant of infante Jorge de Lancastre, a natural son of King John II of Portugal. After graduating at the ...

, the Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

negotiated directly with Sir Benjamin Keene

Sir Benjamin Keene (1697–1757) was a British diplomat, who was British Ambassador to Spain from 1729 to 1739, then again from 1748 until his death in Madrid in December 1757. He has been described as "by far the most prominent British agent in ...

, the experienced British Ambassador to Spain

The Ambassador of the United Kingdom to Spain is the United Kingdom's foremost diplomatic representative in the Kingdom of Spain, and in charge of the UK's diplomatic mission in Spain. The official title is His Britannic Majesty's Ambassador ...

; draft terms were agreed on 5 October 1749, it was not formally ratified until a year later. The ''asiento'' was cancelled and all claims settled in exchange for a payment of ÂŁ100,000 to the South Sea Company, the Cadiz merchants were allowed to resume operations, and Britain received favourable terms for trading with Spanish America.

Provisions

The Treaty contained ten separate articles: Article 1: Britain renounced its claim to the ''asiento'' and the ''Navio de Permiso''; Article 2: Spain paid compensation of ÂŁ100,000, and in return, Britain cancelled any claim to further payments; Article 3: Spain also cancelled claims relating to the ''asiento'' and the ''Navio de Permiso''; Article 4: British subjects would not pay higher (or other) duties in Spanish ports than those prevailing during the reign ofCharles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651, and King of England, Scotland and Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest surviving child of ...

;

Article 5: British subjects would be permitted to gather salt at Tortudos, as they had in the time of Charles II, allowing them to resume fishing operations by using it to preserve fish exported to Britain;

Article 6: British subjects would not pay higher duties than Spanish subjects;

Article 7: Subjects of both nations would pay the same duties, when bringing merchandise into each other's country by land, as they would by sea;

Article 8: Both countries would abolish all "innovations" that had been introduced into commerce;

Article 9: Arrangements were made to integrate the Treaty into the existing treaty system;

Article 10: An undertaking was made to execute the provisions of the Treaty promptly.

Aftermath

Settlement of these issues helped theDuke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne was a title that was created three times, once in the Peerage of England and twice in the Peerage of Great Britain. The first grant of the title was made in 1665 to William Cavendish, 1st Marquess of Newcastle u ...

pursue his policy of improving relations between the two countries, while Keene helped ensure the appointment of a succession of Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

Etymology

The word is derived from the Latin word ''Anglii'' and Ancient Greek word φίλος ''philos'', meaning "frien ...

ministers, including José de Carvajal and Ricardo Wall

Richard Wall y Devereux (5 November 1694 – 26 December 1777) was a Spanish- Irish cavalry officer, diplomat and minister who rose in Spanish royal service to become Chief Minister. He is usually referred to as Ricardo Wall.

Early life

Wall ...

. Although Keene died in 1757, while Charles III of Spain

it, Carlo Sebastiano di Borbone e Farnese

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Philip V of Spain

, mother = Elisabeth Farnese

, birth_date = 20 January 1716

, birth_place = Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Spain

, death_d ...

succeeded Ferdinand in 1759, as a result Spain remained neutral in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754†...

between Britain and France until 1762.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * *{{cite book, last=Simms, first=Brendan, title=Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, year=2008, publisher=Penguin Books War of the Austrian Succession 1750 in Great Britain 1750 in Spain 1750 treaties War of Jenkins' Ear Spanish Empire Madrid (5 October 1750) Madrid (5 October 1750) Madrid (5 October 1750)